Ed. note – Here’s my question: If a ‘shoestring’ operation at a University can figure this out, why can’t the social media companies with all their wealth, power, and AI tools do the same thing? Well, it’s because they don’t want to – that is the only reason. It goes without saying but never retweet or follow those you can’t determine to be who they say they are.

Bot or Not? Online Tools Seek to Cut Through Disinformation Fog

By-

Indiana University offers Botometer, Hoaxy and Botslayer

-

Is @PatriotPurple really a Trump follower named Suzie?

The Twitter account for Suzie, or @PatriotPurple, espoused admiration for President Donald Trump and conservative values. A fist-pumping picture of Trump served as the backdrop, along with a smaller image of a young woman, presumably Suzie, holding an American flag aloft.

There were American flags and a cross, a link to “Patriot Purple News” on YouTube, and a biblical verse: “Because your steadfast love is better than life, my lips will praise you.”

When Pik-Mai Hui, a researcher studying the spread of disinformation on the internet, looked at Suzie’s account, he was reasonably confident that @PatriotPurple was an automated account, or a bot, and that she was part of a coordinated campaign with other bots.

Hui, 27, is part of a team at Indiana University Bloomington’s Observatory on Social Media that has created publicly available online tools to study and understand the spread of disinformation, an increasingly important task as coordinated campaigns threaten to upend elections across the globe, impugn reputations and damage brand names.

Social media giants Facebook Inc., Twitter Inc., and Alphabet Inc.’s YouTube have made efforts to crack down on disinformation campaigns in recent years, as U.S. intelligence officials have warned that adversaries are using influence operations to sow chaos and undermine faith in democracy. But the companies have also been clear that they don’t want to become arbiters of truth.

As a result, a collection of private companies, advocacy organizations and universities, such as Indiana’s Observatory, have stepped up efforts to fight disinformation and developed their own tools to track it, some of which are available to the public.

But tracking disinformation isn’t easy, in part because comprehensive real-time data from social media platforms is expensive to purchase or unavailable. Further, as social media companies, law enforcement and researchers crack down on disinformation campaigns, the groups behind such campaigns — including other governments — evolve their tactics to evade them, according to Ben Nimmo, who leads investigations at Graphika Inc., a firm that uses artificial intelligence to map and analyze information on social media platforms for clients.

“It’s one thing to find behavior that looks potentially suspicious, but it’s another thing to prove that what you’re looking at really is part of an operation, and even harder to prove who’s behind it,” Nimmo said. “External researchers can do that.”

Suzie’s account highlights the challenges. “Not a bot, you obviously need to do more research. Thanks for checking out my feed though. God bless,” she wrote, in response to a direct message on Twitter from Bloomberg News.

But after being asked about @PatriotPurple by Bloomberg News, Twitter permanently suspended Suzie’s account for violating the platform’s manipulation and spam policy.

Suzie’s actions, rather than her content, raised Hui’s suspicions, like deleting batches of her retweets–even hundreds a day. He also pointed out that the accounts she most frequently mentioned or retweeted behaved in a manner consistent with automated accounts.

@PatriotPurple was able to comment on the story because, like many bot accounts on Twitter, some of its actions were likely controlled by a human user, researchers said. These accounts can perform certain activities automated by software, such as retweeting, while others require human intervention, such as posting messages, the researchers said.

@PatriotPurple responds to a Bloomberg News request for comment.

Source: Twitter

Indiana University is a picturesque campus of lush lawns and academic buildings set amid rolling hills, about an hour southwest of Indianapolis and far from the daily news scrums of Washington and New York. The Observatory is located across from a track field, on the third floor of a one-time fraternity house that was renovated for academic use.

Its director, a friendly and efficient 54-year-old Rome-native named Filippo Menczer attributes his interest in disinformation in part to a 2010 lecture he attended at Wellesley College, which focused on fake Twitter accounts used to manipulate a special election in Massachusetts that year. By the 2016 presidential election, when Russian disinformation campaigns sought to provoke political discord in the U.S., Menczer had already developed a significant body of research.

“If you understand misinformation, you can fight it,” said Menczer, who is a professor of informatics and computer science at the university.

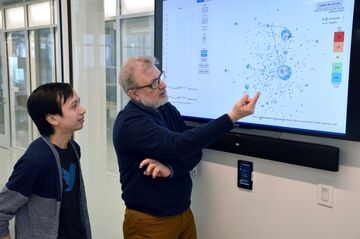

Menczer and Hui with “Hoaxy,” one of the Observatory on Social Media’s publicly available tools for studying disinformation.

Source: Tracey Theriault/Luddy School of Informatics, Computing, and Engineering at Indiana University

His team released its first disinformation tool in 2010, after observing fake campaigns on Twitter during the U.S. midterm elections that year. The tool — which has a newer iteration — sought to visualize the spread of trending topics in order to help people see whether they were spreading in a manipulated way.

Since then, Menczer’s team has created additional tools to broaden their accessibility to journalists, civil society organizations, and other interested users, as well as keep up with increasingly sophisticated disinformation campaigns across social media.

One of the group’s tools is called “Botometer,” and it assigns any Twitter account a score, from one to five, denoting how likely it is to be a bot based on its behavior (a five is most bot-like). Suzie’s account, for instance, scored a 4.5. That’s a sharp contrast to the accounts of the top two Democratic candidates, Bernie Sanders and Joe Biden, who both scored a 0.3 on Botometer on the morning of Super Tuesday. Trump’s Twitter account was considered even less bot-like that day: 0.2 on Botometer.

Another tool developed in Indiana is called “Hoaxy,” and allows a user to map the flow of claims spreading online. Each account is color-coded by its Botometer score. For example, the Hoaxy results suggest both that Trump’s Twitter account has been central to spreading the claim that CNN produces fake news and that a range of human and bot-like accounts have amplified that allegation.

Meanwhile, utilizing a tool called BotSlayer, users can watch Tweets in real time on a given topic — such as the top presidential candidates — allowing them to spot disinformation campaigns as they unfold.

In 2018, the tools were used by representatives from the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee to track a disinformation campaign aimed at suppressing voter turnout in the U.S. midterm election through claims that male Democrats shouldn’t vote because doing so would overpower female voices. The committee reported its findings to Twitter, Facebook and YouTube, which removed bots as a result, according to a committee spokeswoman.

But some have raised questions about the disinformation tools. A Twitter representative said tools relying on the public information available to developers can be ineffective at distinguishing bots from human users. The representative said Twitter seeks to remove malicious or bot-like accounts.

Some conservative media outlets have accused the project of having a liberal bias, a charge Menczer denied in a blog post.

He also pointed out that the tools have rooted out disinformation on both sides of the aisle. For instance, the researchers recently found an apparently coordinated bot campaign using the hashtag #BackFireTrump that was pushing gun control, including using misleading reports of shootings, Menczer said.

Beyond the hurdle of researching a politically sensitive topic, Menczer’s group must bear the considerable expense of purchasing and maintaining company data. To conduct its disinformation research, the university purchased access to a stream of data containing 10% of all public tweets, known as the “Decahose.” (The more expensive “Firehose” includes the content and context of all tweets.) The cost of the data isn’t publicized because Twitter requires its data customers to sign non-disclosure agreements about pricing.

Facebook and YouTube don’t offer the same kind of raw data stream. That means Menczer’s team studies a slice of Twitter data, and then checks whether similar disinformation campaigns are running on other social media platforms.

“We have to find funding for the [Twitter] data and of course we wish we didn’t have that hurdle,” said Menczer. “But at least it is available and that’s more than you can say about the other platforms.”